Editing a Novel vs. Editing a Feature Story: Same Steps, Different Goals

Part I: The Four Types of Editing

Why Editing Needs Clear Definitions

One of the most common confusions among writers is the difference between the types of editing. Ask five people and you may get five answers: “Developmental editing is structure,” “Line editing is grammar,” “Copyediting is just proofreading.” In truth, each of these labels describes a specific layer of intervention that builds on the one before it.

The order matters. If you try to polish sentences before you’ve solved structural flaws, you waste time. If you proofread before the copyedit, you’re smoothing over errors that will just shift again. Editors know the stages. Writers who understand them write better — and hire or self-edit more effectively.

While the four stages — developmental, line, copy, proof — are the same in principle across genres, the way they are practiced differs between novels and feature articles. A novelist works in long arcs of character and plot, across tens of thousands of words. A feature writer works in shorter arcs of leads, nut grafs, scenes, and kickers, balancing accuracy with narrative. Both rely on narrative movement, but the goals and constraints differ.

1. Developmental (Structural) Editing

Novels

In novels, a developmental edit looks at the big picture of story. Are the characters compelling? Is the plot coherent? Does the pacing carry the reader, or sag in the middle? Are subplots integrated or distracting?

Developmental editing in fiction often involves tearing down and rebuilding. An editor might suggest cutting whole chapters, reordering scenes, or deepening character motivations. The developmental editor asks questions like:

What does the protagonist want, and what obstacles stand in the way?

Does the story escalate toward a climax?

Are there scenes that exist only to convey information, but do not advance the plot?

Because novels can run 70,000–100,000 words or more, the developmental edit ensures the architecture of the story holds. Without it, beautiful sentences sit on shaky ground.

Feature Stories

For feature writing, developmental editing serves a parallel but distinct role. Instead of plot, the editor looks at narrative arc within a real-world frame. William Blundell, in The Art and Craft of Feature Writing, insists that even factual stories must have a spine — a sequence of movement that keeps the reader turning the page.

In features, the big-picture concerns include:

Does the lead draw the reader in?

Is there a clear nut graf — the paragraph that explains why this story matters, why now?

Are the scenes ordered to build tension, clarity, or resonance?

Do voices and quotes support the story’s arc, or clutter it?

A developmental edit in a feature story might reorder whole sections: moving a vivid anecdote up to serve as the lead, condensing background into the nut graf, and pushing analysis or statistics further down. It might also recommend new reporting — “You need a stronger voice from the community” — the nonfiction equivalent of adding a missing subplot.

Narrative Arcs in True Stories

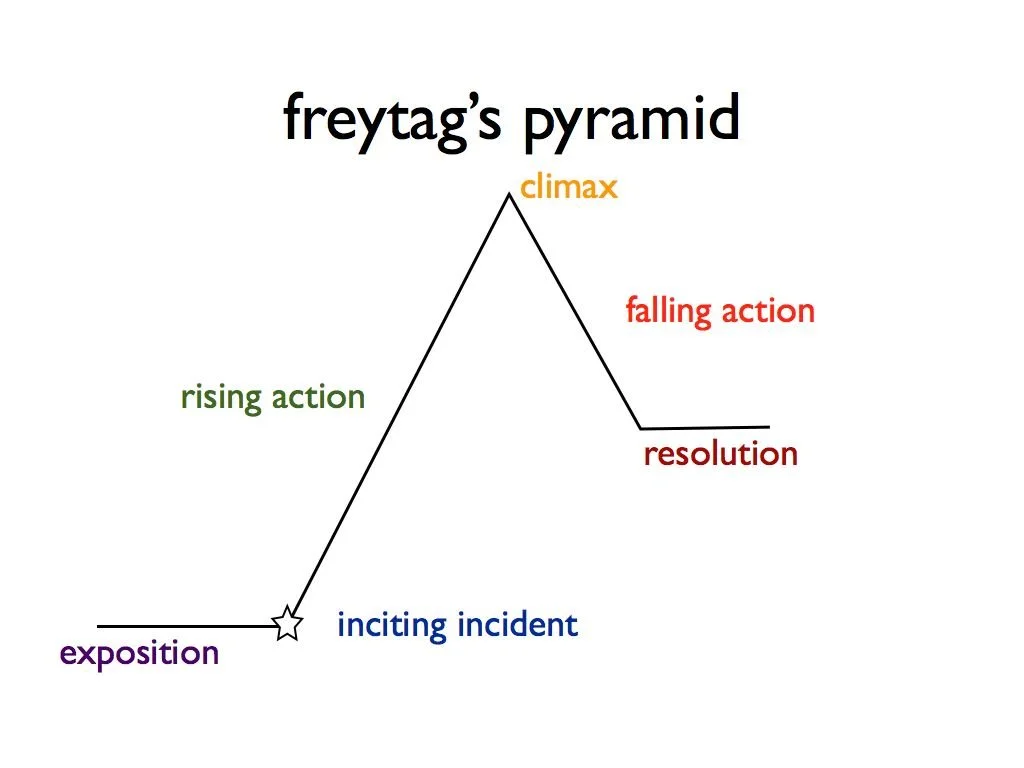

Both novels and features require arcs, but their arcs operate differently. In fiction, the arc usually follows Freytag’s triangle: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution. In features, the arc is often modular: lead, nut graf, body sections, kicker. Yet the purpose is the same: readers crave movement.

Bruce Garrison, author of Professional Feature Writing, stresses that true stories without shape feel aimless. Narrative editing in nonfiction is the act of carving meaning from raw reality. That’s the essence of developmental work in features: shaping life into a readable arc without falsifying it.

2. Line Editing

Novels

Once the story’s structure is sound, line editing dives into the sentence level. Line editors work with rhythm, clarity, tone, and style. In a novel, this may mean:

Shaping sentences to mirror a character’s internal state.

Trimming purple prose to sharpen impact.

Adjusting imagery for consistency.

Shifting clunky exposition into graceful dialogue.

A novel’s line edit is deeply tied to voice. The editor must preserve the author’s style while refining it. Every sentence should serve story and character.

Feature Stories

For features, line editing emphasizes clarity and momentum. Blundell advises that every sentence in a feature should “carry story weight.” This means:

Cutting jargon or bureaucratic phrasing.

Trimming quotes to their sharpest phrasing without distortion.

Ensuring transitions between scenes are smooth.

Balancing narrative description with factual information.

Line editing in journalism often means compression. A novelist may luxuriate in three paragraphs of description; a feature writer must deliver a sense of place in two sentences. The editor trims without losing texture.

Shared Principle

Whether in novels or features, line editing asks: does the sentence move the reader? If not, it goes. In both forms, rhythm is king: a novel might vary long lyrical passages with short dramatic bursts; a feature might weave direct quotes with crisp narration.

3. Copyediting

Novels

In novels, copyediting focuses on mechanics and consistency. This includes:

Grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

Consistency of names, places, timelines.

Stylistic rules (Oxford comma or not, italics vs. quotation marks for thought).

Copyeditors for novels ensure the book is internally coherent. They rarely check external facts unless it’s historical fiction or nonfiction elements.

Features

In journalism, copyediting carries heavy weight. In addition to grammar and style, copyeditors check:

Factual accuracy: dates, names, statistics, quotes.

Consistency with style guides (AP, Canadian Press, house style).

Ethical clarity (e.g., avoiding loaded descriptors).

Headline and subhead accuracy.

Sue Pape and Sure Featherstone, authors of Feature Writing: A Practical Introduction, point out that credibility rests on the copy desk. Unlike fiction, where a slip in continuity is embarrassing, in nonfiction it can be libelous or damaging to public trust. Copyediting in features is both linguistic and ethical.

4. Proofreading

Novels

Proofreading is the last line of defence before publication. It checks:

Typos, spelling errors.

Formatting glitches (widows, orphans, page breaks).

Consistency of headers, footers, chapter titles.

It’s the “safety net” — minor but crucial.

Features

In journalism, proofreading often happens at speed. A final read may occur minutes before going to press. It includes:

Typos and grammar.

Caption errors under photos.

Pull quotes and sidebars.

Page layout issues.

Because of tight deadlines, proofreading in features is sometimes merged with copyediting. But the function is the same: catch errors before readers do.

Putting It Together: The Four Layers as a System

Seen side by side, the stages look like this:

Stage Novels Features Developmental Plot, character, pacing Lead, nut graf, story spine Line Voice, rhythm, imagery Clarity, compression, flow Copyediting Grammar, continuity Grammar, accuracy, style, facts Proofreading Typos, layout Typos, captions, headlines

Each layer builds on the one before it. Skip developmental and your sentences polish an unstable frame. Skip line editing and your facts sit in clunky prose. Skip copyediting and your errors erode trust. Skip proofreading and a single typo mars professionalism.

Insights from the Feature Writing Texts

Garrison emphasizes that editing in features is part of reporting: sometimes you discover during the developmental edit that you need more voices or data. Unlike novels, the story material is not all under your control.

Blundell stresses that structure and sentence weight are inseparable in features — narrative spine and line-by-line clarity work hand in hand.

Pape & Featherstone highlight the ethical role of copyediting and the importance of sensitivity in language, which resonates with conscious editing in fiction as well.

The four types of editing are shared tools across genres. What differs is application: novels build imagined worlds, features shape reality. Both need narrative arcs, both need clean sentences, both need accuracy (though in different senses). For the novelist, editing ensures immersion and coherence. For the feature writer, editing ensures truth and engagement.

Editing is not just correction. It is craft at multiple levels — architectural, stylistic, factual, and cosmetic. Understanding the differences between novels and features in these four layers helps writers move between the two worlds with confidence.

Part II: Narrative Arcs in Fiction and Nonfiction

Why Arcs Matter

Stories without arcs feel like driftwood: they may float, but they never reach a shore. Readers intuitively sense when a story is going somewhere, when the momentum is pulling them forward. That pull is the arc — the shape of movement from beginning to end.

Novelists and journalists both work with arcs, though their raw material differs. Novelists invent characters, conflicts, and resolutions. Feature writers gather facts, interviews, and sensory detail from real life. Yet both must carve those materials into arcs that provide coherence, pacing, and payoff.

Bruce Garrison points out that even “true stories” require a skeleton of structure. William Blundell argues that without a story spine, features collapse into disorganized facts. Pape & Featherstone remind students that every feature must answer: why now, why this, why should the reader care? That answer sits at the heart of the arc.

Arcs in Novels: The Traditional Models

Freytag’s Pyramid

In fiction, the best-known arc is Freytag’s Pyramid: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution. Not every novel follows this rigidly, but most echo its rise and fall.

Exposition: Establishing characters, setting, stakes.

Rising Action: Conflicts intensify, obstacles accumulate.

Climax: A turning point where tension peaks.

Falling Action: Consequences unfold.

Resolution: Loose ends tied, or intentionally left open.

Alternatives

The Hero’s Journey: Joseph Campbell’s circular arc of departure, initiation, and return.

Three-Act Structure: Setup, confrontation, resolution — widely used in modern novels and screenplays.

Fragmented or Nonlinear Arcs: Postmodern novels experiment with fractured timelines, but still rely on an underlying sense of motion.

The Role of Editing

Developmental editing in novels ensures that the chosen arc is working in practice. If a middle section drags, the edit trims or reorders events. If the climax lacks impact, the edit deepens stakes earlier. The line edit then aligns prose rhythm with arc: short, sharp sentences in moments of tension; longer ones in reflective lulls.

Arcs in Feature Stories: Shaping Reality

Feature writers cannot invent characters or plot twists. Their raw material is reality. Yet reality is messy. Interviews ramble. Events overlap. Data points contradict. The developmental and line edits impose shape.

The Classic Feature Arc

Most features use a modular arc rather than a pyramid. The elements include:

The Lead: An anecdote, description, or scene that hooks the reader.

The Nut Graf: The paragraph that explains the point — why this story, why now.

The Body: Organized into sections or scenes, each building on the last.

The Kicker: A closing that resonates — a quote, image, or callback.

This is less about climax and resolution than about curiosity and closure. The arc keeps readers engaged while delivering information.

Variations

Anecdotal Lead → Nut Graf → Thematic Sections → Reflective Kicker

Narrative Lead → Chronological Progression → Outcome

Explanatory Arc: Start with a question or mystery, unfold evidence, conclude with insight.

Blundell’s “Story Spine”

Blundell insists every feature must have a “spine” — a throughline that holds disparate facts together. Without it, readers drown in data. The editor’s job is to identify and reinforce this spine: perhaps it’s a single character’s journey, or the evolution of a community problem.

Garrison’s Emphasis on Structure

Garrison highlights that the nut graf is non-negotiable. Unlike a novel, which may bury themes subtly, a feature must tell readers why they’re reading within the first few paragraphs. The nut graf anchors the arc.

Challenges of Arcs in True Stories

The Risk of Over-Imposing

Editors must balance narrative shape with factual truth. If you twist reality too hard to fit a perfect arc, you risk distortion. Garrison warns against “novelizing” facts. Ethical feature writing means finding shape without fabricating.

The Problem of Open-Endedness

True stories often lack neat resolutions. A novel ties threads; a feature may close with uncertainty. The kicker often reflects that ambiguity — a lingering question rather than a solved equation.

The Editor’s Hand

Here, developmental editing is critical. Editors help writers choose which details support the arc and which clutter it. They encourage cuts that serve coherence. They may ask for new reporting to fill gaps in the spine.

Shared Lessons Between Genres

From Novels to Features:

Novelists know how to sustain tension; feature writers can learn pacing from fiction.

Novelists explore character motivation; features can borrow that depth for profiles.

From Features to Novels:

Feature writers know compression; novelists can learn concision from journalism.

Features demand clarity; novelists can use journalistic discipline to keep plots tighter.

Universal Lesson:

All stories need momentum. Whether it’s a protagonist chasing love or a journalist explaining climate change, arcs keep readers reading.

Editing Arcs: Practical Tools

For Novels: Storyboards, beat sheets, timeline maps.

For Features: Outline with lead, nut graf, body sections, kicker.

For Both: Ask “What’s the emotional journey for the reader?” Editing arcs is editing emotion.

Narrative arcs are the editor’s compass. In novels, the arc sustains immersion across hundreds of pages. In features, the arc organizes messy reality into meaning. Both require developmental intervention and line-level finesse. Both serve the same purpose: to move the reader.

Part III: Applying the Tools Across Genres

Why Cross-Pollination Matters

Novelists and feature writers often live in separate worlds. The novelist dwells in imagination and invention; the feature writer in fact and observation. Yet both are storytellers working under the pressure of engaging an audience. Editing reveals their shared DNA.

The four stages of editing — developmental, line, copy, proof — expose similar needs. Both require arcs. Both demand clarity. Both rely on the reader’s willingness to follow a thread from first sentence to last. What differs is emphasis: novelists privilege immersion; journalists privilege precision. When these disciplines borrow from one another, each grows stronger.

As Blundell puts it, “features borrow the pleasures of fiction to explain the truths of fact.” The reverse is also true: fiction borrows compression and discipline from nonfiction.

1. Developmental Editing: Borrowing the Big Picture

What Novelists Can Learn from Features

Compression of structure: Features must deliver purpose early, often through the nut graf. Novelists can benefit from asking: What is my story about? Why should readers care — now? Introducing thematic stakes earlier can prevent sagging openings.

Audience awareness: Features are edited with readers in mind at every turn. Developmental editing in journalism is about clarity and relevance. Novelists can adapt this mindset by ensuring each chapter advances not just plot, but the reader’s experience.

What Feature Writers Can Learn from Novels

Character arcs: Novels excel at building motivation, desire, and transformation. Profiles and narrative features can borrow this depth. A developmental edit might ask: Does the reader see growth or change in this subject?

Scene layering: Novelists braid subplots. Feature writers can echo this by weaving multiple threads (personal anecdote, data, expert analysis) into a single arc without fragmentation.

Shared Editing Checklist for Developmental Work

Does the story have a spine (plot/nut graf)?

Do scenes build tension and momentum?

Are character motivations or subject stakes clear?

Is there a satisfying payoff or resolution (or intentional ambiguity)?

What can be cut without harming the spine?

2. Line Editing: Sentence by Sentence

Lessons Novelists Can Borrow

Concise expression: Feature writers know how to condense a scene into a paragraph without losing vitality. Line edits in novels can look to journalistic concision to cut filler and tighten prose.

Impact leads: Journalists write ledes that seize attention. Novelists can study these to strengthen chapter openings or hooks.

Lessons Feature Writers Can Borrow

Rhythm and music of language: Novelists know how sentence length and cadence shape mood. Features can become more immersive when line editing considers rhythm beyond information delivery.

Voice preservation: Novelists guard character voices. Journalists can bring the same care to quoted sources, ensuring they speak with texture rather than as soundbites.

Example: Novelistic vs. Journalistic Line Editing

Original (novelistic draft):

The sky over the prairie was a canvas smeared with pastels, the sun dragging long fingers of orange and violet into the horizon, while the grass bent like worshippers in the evening wind.

Edited with feature discipline:

As the sun set, orange light stretched across the prairie. The wind pushed the grass flat.

Both describe the same moment. The first aims at immersion and lyricism; the second aims at clarity and compression. The lesson: editors should know when to borrow each mode.

3. Copyediting: Accuracy and Continuity

Novels

Copyediting ensures internal truth: consistent names, timelines, settings. A novel cannot have a blue-eyed character in Chapter 1 and brown-eyed in Chapter 10 — unless intentional.

Features

Copyediting ensures external truth: facts, quotes, statistics. A misspelled name or incorrect date undermines credibility.

Cross-Genre Lessons

Novelists learning from features: Fact-check your invented world with the same rigor a journalist uses for reality. Continuity errors break immersion. Use a style sheet (characters, timelines, invented terms).

Feature writers learning from novels: Guard narrative continuity. Just as a novel must align details, a feature must align reported facts across drafts and edits.

4. Proofreading: The Final Safety Net

Shared Concerns

Both novels and features rely on proofreading for professionalism. Typos may not destroy meaning, but they damage trust. Readers subconsciously assume carelessness in words equals carelessness in ideas.

Distinctions

Novels: Proofing often includes page design issues — widows, orphans, layout polish.

Features: Proofing includes captions, headlines, pull quotes — small elements that readers see first.

Shared Lesson

Editors in both fields must recognize that presentation matters. A typo in a novel or a garbled caption in a feature erodes credibility.

5. Transferrable Editing Skills

For Novelists

Borrow the nut graf mindset: clarify early what the story is about.

Adopt fact-checking discipline for continuity.

Practice cutting with journalistic brevity.

For Feature Writers

Borrow the arc mindset: treat subjects as characters with goals and obstacles.

Use rhythm and imagery from fiction to enliven prose.

Value immersion alongside information.

6. The Role of the Editor as Translator

Editors often act as translators between worlds: turning raw reporting into narrative, or turning sprawling drafts into structured novels. The skill is the same — finding story, shaping sentences, ensuring accuracy. The difference is emphasis.

As Pape & Featherstone argue, editing is not mechanical correction but an act of meaning-making. Garrison adds that for journalists, editing is reporting: you may discover missing facts in the edit. Novelists face the same reality with imagination: gaps in structure discovered in editing demand invention or rethinking.

The four editing stages become powerful when applied across genres. Novelists gain clarity and discipline by borrowing journalistic techniques. Feature writers gain depth and resonance by adopting novelistic tools. Both discover that editing is not a wall between fiction and nonfiction but a bridge.

The result is better stories: true or imagined, precise or expansive, but always engaging.

Part IV: Beyond the Four Types

Why We Need More Than Four

The four classic stages — developmental, line, copy, proof — give us a strong editing framework. But in practice, especially today, they’re not enough. Writers and editors face new challenges: ethics, representation, digital platforms, and multimedia storytelling. These require additional forms of editing layered on top of the traditional ones.

As Garrison notes, journalism’s responsibility is not just accuracy but trust. As Blundell warns, structure without ethical clarity is hollow. And as Pape & Featherstone emphasize, editing is an act of responsibility toward both subjects and readers.

1. Sensitivity and Conscious Language Editing

Novels

Representation matters: Editors must examine whether portrayals of race, gender, sexuality, or disability rely on stereotypes.

Language evolves: Terms once accepted may now wound. Editors must help writers navigate respectful, accurate usage without flattening voice.

Own voices vs. outside perspectives: Editors may ask whether a story speaks authentically or appropriates.

Features

Source framing: How subjects are described matters. Labeling someone a “victim” versus “survivor” shifts tone.

Community voice: Editors ensure that marginalized voices are not tokenized but integrated with depth.

Trauma-informed editing: How interviews with survivors are presented demands care — avoiding re-traumatization or sensationalism.

Shared Principle

Editing is about more than mechanics. It’s about responsibility to people represented in words. Conscious language editing ensures stories honor lived realities.

2. Fact-Checking as Its Own Stage

Novels

Historical or science fiction often requires external accuracy: Did this technology exist in 1920? Could this journey be done in a day? Editors encourage research that grounds imagination.

Even purely fictional worlds need internal fact-checks: Are invented terms spelled consistently? Does invented technology follow its own rules?

Features

Fact-checking is non-negotiable. Every name, date, and quote must be verified. A misquote is not just sloppy — it can be defamatory.

Good fact-checking often requires going beyond the writer: calling back sources, re-checking statistics, confirming with secondary data.

Shared Lesson

Fact-checking deserves recognition as its own editing pass. It may be embedded in copyediting, but treating it as distinct ensures it receives the attention it demands.

3. Style Sheets: The Editor’s Map

Purpose

A style sheet is a living document that tracks decisions: spelling, capitalization, punctuation, character details, timelines.

Novels

Tracks character names, traits, ages, and continuity.

Records invented terms or languages.

Notes stylistic choices (italics for thoughts, hyphenation patterns).

Features

Tracks spelling preferences (U.S. vs. Canadian spelling, proper nouns).

Ensures consistent reference to organizations, titles, or acronyms.

Tracks terminology for sensitive issues (e.g., “Indigenous” vs. “Aboriginal”).

Benefit

Style sheets ensure consistency across drafts and across editors. They’re a simple but overlooked part of editing craft.

4. Digital and Multimedia Editing

The New Landscape

Editing no longer ends on the printed page. Blogs, online magazines, and multimedia features introduce new tasks:

SEO Editing: Keywords, meta descriptions, headings. Writers must be found before they can be read.

Visual Editing: Captions, alt-text, infographic clarity.

Multimedia Arcs: When a feature includes video, photo, or interactive graphics, the editor ensures narrative coherence across mediums.

Novels in Digital Spaces

Self-publishing platforms demand formatting consistency (ePub, Kindle).

Audiobooks require line-level edits for sound clarity.

Online excerpts require SEO-friendly intros.

Features in Digital Spaces

Online features must be scannable: subheads, pull quotes, bullet points.

Editors balance narrative flow with digital readability.

Ethical editing extends to images: choosing photos that respect subjects.

5. Ethical Editing as the Umbrella

Across both fiction and nonfiction, editors confront ethical dilemmas:

Should a novelist write from a perspective they do not share?

Should a feature writer include a detail that is true but may endanger a source?

How much cutting of a source’s quote is ethical before distortion occurs?

Ethical editing asks not just can we but should we. It requires transparency, humility, and dialogue with writers.

6. Editing as Collaboration

Blundell stresses that editing is not adversarial but collaborative. Garrison describes editing as “continuing the act of reporting.” Pape & Featherstone remind us that editing is teaching: guiding writers toward sharper skills.

The best edits are not red marks in isolation. They are conversations, shaping not just this piece but the writer’s growth.

Practical Additions to the Editing Toolkit

Sensitivity Checklist: Have we avoided stereotypes, tokenism, harmful phrasing?

Fact-Check Log: Each name/date/source confirmed, with citations.

Style Sheet: Living document updated draft by draft.

Digital Checklist: SEO title, meta description, alt-text, headings.

Ethical Reflection: Does the edit serve the truth and the people represented?

Editing is bigger than four categories. It is a layered act of responsibility. Novels and features alike require not only developmental structure, stylistic clarity, mechanical precision, and proofreading, but also ethical, factual, stylistic, and digital awareness.

The editor’s task is no longer only about sentences — it is about systems of meaning, trust, and access. The stories we publish shape cultural memory. Editing ensures they do so with integrity.

Part V: Conclusion — Editing as the Bridge Between Story and Reader

The Thread That Holds It All

Editing, whether in fiction or nonfiction, is often described in mechanical terms: correcting grammar, polishing sentences, cutting excess. But over these sections we’ve seen it is much more: an act of shaping, guiding, and safeguarding the reader’s journey.

The four traditional categories — developmental, line, copy, and proof — give us a sturdy framework. But when we examined how those apply differently to novels and features, we saw that editing is about narrative movement: ensuring both imagined and true stories have arcs that carry readers along. We expanded outward to include sensitivity, fact-checking, style sheets, and digital editing — all crucial in today’s publishing landscape.

What emerges is not a hierarchy of corrections, but a holistic system: editing as the bridge between what a writer intends and what a reader experiences.

Shared DNA of Novels and Features

At first glance, novels and features seem worlds apart. One thrives on invention, the other on fact. One lives in long, immersive arcs; the other in compressed, modular sections. But under the editorial lens, their kinship becomes clear:

Both require narrative arcs to sustain attention.

Both demand clarity at the sentence level.

Both rely on accuracy — internal continuity for novels, external fact-checking for features.

Both succeed or fail on the strength of their final polish.

The distinctions are important, but the overlaps are powerful. Editing reveals that storytelling, regardless of form, shares the same fundamental heartbeat.

The Expanding Role of the Editor

Today’s editor is no longer just a red pen. They are:

Architect: shaping developmental arcs.

Stylist: refining line-by-line rhythm.

Guardian: ensuring factual and ethical accuracy.

Technologist: preparing stories for digital spaces.

Advocate: representing both writer and reader, ensuring trust and respect.

This expansion does not diminish the traditional roles but enhances them. It reminds us that editing is dynamic, evolving with technology and culture.

What Novelists Can Take Away

Learn the discipline of clarity from journalists. Ask yourself: Could I explain the stakes of my novel in a nut graf?

Embrace fact-checking and continuity editing as rigorously as a newsroom.

Value compression: learn how to convey in one paragraph what might otherwise sprawl across three pages.

What Feature Writers Can Take Away

Borrow narrative arcs from fiction: treat profiles and features as character-driven stories.

Embrace rhythm and imagery, not just information. A well-edited sentence can sing, even in nonfiction.

Remember immersion: journalism is not only about data but about carrying readers into lived experience.

Editing as an Ethical Act

Perhaps the most important conclusion from this exploration is that editing is not neutral. Every cut, every word choice, every rearrangement carries ethical weight. Editors decide what readers see and how they see it. That power demands humility and responsibility.

For novels, this means editing with respect for cultures, identities, and experiences not your own. For features, it means protecting accuracy, honoring sources, and avoiding harm. In both cases, editing is a moral practice as much as a craft.

The Future of Editing

As we move further into a digital age, editing will continue to evolve:

AI tools may catch typos or suggest cuts, but cannot replace human judgment about narrative, voice, or ethics.

Cross-genre editing will become more common, as writers shift between memoir, reported essays, and hybrid forms.

Multimedia storytelling will demand editors who can shape arcs across text, image, sound, and interactivity.

But at the heart of all this change remains the editor’s core task: ensuring stories connect with readers truthfully, clearly, and powerfully.

A Final Word

Editing is not the enemy of creativity but its companion. It is not subtraction but refinement. To edit is to respect both writer and reader: to honor the messy draft while carving a clearer path forward.

For novelists, editing keeps the imagined world coherent and compelling. For feature writers, editing shapes reality into meaning. For all writers, editing is the assurance that stories do not merely exist, but live in the minds of readers.

If there is one truth that holds across all genres, it is this: editing is storytelling’s second act. The first draft creates the raw clay; editing shapes it into form. And when done well, editing ensures that stories — whether of imagined worlds or real lives — do what they are meant to do: move us, change us, and stay

Open any report and you’ll see the problem: a wall of numbers. Percentages, graphs, trend lines. Useful, yes — but for most readers, lifeless. Raw data has the strange effect of shutting our eyes even as it tries to open them. We know the figures matter, but without context, they rarely move us.